First, I must tell you that I am absolutely not a Martial Arts specialist.

I do not write this article with a fighting experience nor as an experienced practitioner: to my credit I only have one single year of Karate Shotokan practice as a teenager – supplemented, it is true, by the viewing of the complete Bruce Lee filmography and an ephemeral passion for the nunchaku 🙂

On the other hand, over the years, I have acquired a sensitivity to Martial Arts through the practice of my wife, Aïkido black belt, and the training and competitions of my two sons (in Judo, Ju Jitsu, Vo Vinam and Kudo).

Since I started teaching Yoga, I had the chance to give classes at Kudo and Muay Thaï clubs in Rennes, and to really identify the close links existing between Martial Arts and Yoga – that’s the purpose of this article.

Note that I do not make any distinction between “Combat Sports” and “Martial Arts”, I consider that in practice the differences – when they exist – are specific to the disciplines and especially to the coaches / masters who teach / transmit them. To illustrate my point: in my opinion, a very competition oriented Judo club will for example be less in the “Martial Art” path than an “old-fashioned” boxing gym transmitting the noble Art respect and self surpassing values to young people struggling with social difficulties.

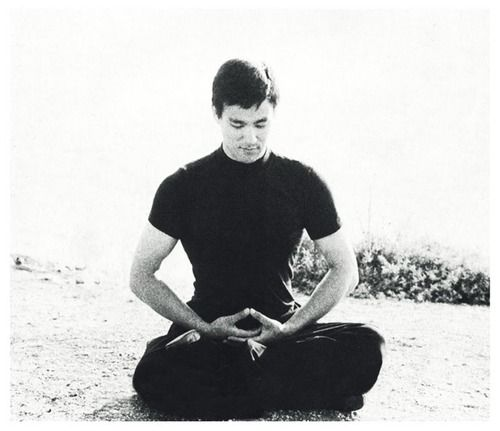

![]()

Dealing with an external threat through flight or fight is a common feature of all living things. The protection of the territory and its resources, fighting for the partner, or against predators, are behaviors that are immemorially inscribed in our genes, transmitted and refined at each stage of the evolution.

Martial Arts represent the techniques developed by the human species to optimize or even transcend these behaviors.

It is said that the evolved form of Martial Arts takes shape in Asia fifteen / twenty centuries ago, from India to China and Japan.

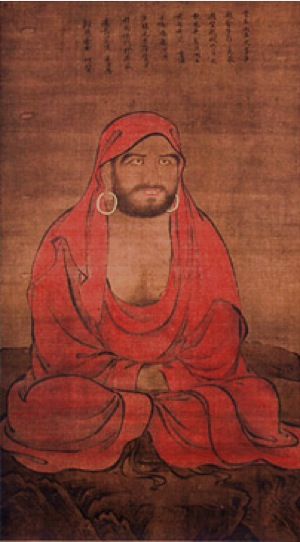

At this point of our history, Chinese Buddhist monks (from the legendary Shaolin Temple) make warlike preparation techniques their own to enhance their vitality under the influence of Bodhidharma, an Indian itinerant monk keen on Kalaripayat and Yoga. Thus, they can both protect themselves from bandits and bring their bodies to better withstand the required immobility during the long sitting meditation sessions.

This is the starting point of the virtuous circle between martial and spiritual practices which later migrated to feudal Japan.

The Warrior’s path requires a total involvement of the Being, at all levels: body, mind and spirit. The spiritual component is certainly the most important because it cements the physical and mental capacities: the Crusader Knight, like the Viking or the Samurai, integrates the meaning of his life into a pattern that is way beyond him. By getting free from the fear of death, their being was totally at the service of combat, being then most effective on the battle field.

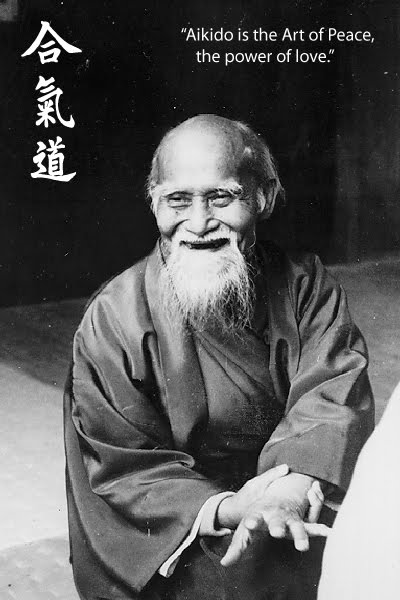

Paradoxically enough, the finality of Martial Art appears over time as the ability to avoid war. The practitioner develops the ability to fight the enemy – or the adversary – and therefore to postpone the fight, or even to force to negotiation. In parallel, advancing in his practice allows him to identify and channel his own impulses, further reducing the likelihood of confrontation.

The Martial Arts become a vector of peace.

The object of Yoga is to free us from our conditioning that prevent us from fully being in the moment. As soon as we become totally present to ourselves and to what surrounds us, the agitations of our mind subside and we can then See our real Nature, in full alignment with the world.

Throughout generations and master-to-student transmissions, Yogis refined a great variety of body, breath and mental techniques for this purpose. Tearing the veil of our illusions, getting rid of automatic thought patterns requires a real form of struggle, an inner one.

To establish a state of peace within ourselves, an Union with the universe, a total acceptance of what is, is neither trivial nor immediate. The attainment of Yoga objectives requires intense and repeated efforts over a long period – it is truly a form of combat.

Martial Arts practice takes a multitude of forms according to the style and to the teacher (or master) sensitivity, but there are constants.

In the first place, discipline, formalized in many schools (or clubs) by a code of conduct, which involves the student in a respectful and assiduous attitude. It can be seen that these codes of conduct – or code of “honor” like bushido – are quite close to Patanjali Yoga Sutras Yamas and Niyamas.

Then, the development of the practitioner physical qualities : technique, strength, flexibility, speed, balance and endurance are trained in the school style.

Here too one can find common points, especially around the “just gesture” notion : a subtle mix of strength and relaxation that brings speed and fluidity to the movement.

But also the quality of presence in the moment, which allows for the optimal anticipation of the adversary behavior : sharp observation, dodging, swift counter attack decision… These qualities are often worked in sparring.

Breath work is less systematically present, but takes a prominent place in certain disciplines, such as in Shotokan karate katas.

Finally, on the mental plane, beyond the concentration on the body and breath, the fighter must control the emotions that can put his effectiveness in danger: essentially fear and anger.

There, it is through real situations (fights / sparring) or virtual situations (katas) that the practice takes place.

Sometimes in some schools a moment of relaxation and / or meditation is also proposed at the end of the training.

We can see that the overlap of Martial Arts training with Yoga is quite complete: work on the body, breath and mind with even many similar exercises.

I have already detailed the practice of Yoga quite a bit in this blog 🙂 but I wish to remind here some essential themes that can resonate to Martial Artists ears.

In Yoga we aim to anchor, balance and loosen up the body so that it steadily becomes more efficient. By statically holding and moving through unusual daily life body poses, the Yoga practitioner develops his inner sensations and build subtle muscle and limb positioning control.

By observing bodily sensations and breath, one learns the importance of fluid and conscious breathing, and thus on how to avoid or undo muscular tensions: creating space in the body to better relax, breathing.

Recognizing, then getting rid of bad postural patterns by activating certain neglected areas and releasing other overused ones soothes the mind, balances the body and promotes injury prevention.

Body work in Yoga is rather static, in the immobility of a given pose, but can also integrate dynamic sequences synchronized with the breath. It is then an opportunity for the practitioner to trap body tensions a little differently, to feel the importance of proper center positioning (Hara) and to observe how breath can efficiently precede movement.

The discovery and mastery of the 3 main bandhas, muscle zones located along the spine, will in turn contribute to a better understanding and appropriation of efficient body positioning and motion.

In a dynamic Yoga practice, the diaphragm is one of the primarily targeted muscles. In Pranayama, beyond the bandhas, it is even the only muscle one seeks to work.

Breath work in Yoga allows in particular

– Improvement of the thoracic cage tissues flexibility and diaphragm contractile quality : increase of the exchanged gas volume

– Respiratory rate slow down : better energy efficiency, increased cardiovascular capacity

– Autonomic nervous system balancing by strengthening the para sympathetic axis: better recovery and emotional control

Constantly bringing the attention back to the body sensations, controlling its positioning in space, remaining present to the breath quality: it is a permanent work of concentration and neurological learning. Yoga develops the understanding of micro muscular movements allowing for subtle body positioning, especially useful for technical learning and “right gesture” appropriation – Stiram Sukham Asanam.

This intense work of concentration brings the experienced practitioner into a state of meditation, occurring when concentration no longer requires any effort, when it simply is happening on its own. Then, little by little, it becomes possible to get detached from emotions and to observe them expressing themselves in us. To study ourselves on the mat during practice, as well as off the mat. To observe thoughts and identify mental patterns, to gradually develop consciousness of the body / breath / mind triptych, and awareness of being conscious.

Finally, usually happening at the end of the Yoga session, a moment of relaxation allows for a conscious experience of a total letting go, a surrender of the self – the relaxation of the body preceding a possible expansion of the Being. On the physical plane, relaxation is synonymous to recovery, as are the inversion poses that often precede it.

Martial Artists can use Yoga techniques to improve their training quality, with a goal of value directly transferable to combat – especially to fill aspects of the body / breath / mind triptych that would be insufficiently trained in their discipline.

But I think Yoga can also – and mostly – allow Martial Artists to make the finality of their discipline more tangible to them and thus contribute to their overall development and well being by pacifying themselves.

Bring spirituality back to the center of the fight.

![]()

There are many common points between Yoga and Martial Arts, we can legitimately ask ourselves if they pursue the same goal?

To me the answer is clearly yes, namely the control or even the suppression of the struggle and domination instincts that have forever agitated our species, to somehow sign the end of the ego supremacy in ourselves – it is anyway quite difficult to consider humanity existence by the end of the century if we do not get out of our navels, we will probably have disappeared thanks to the approaching ecological disaster.

To realize that the other is like me, to See that the other and I have exactly everything in common, that is what gives meaning to my Yoga practice, to my life.

Practicing a martial art proceeds exactly with the same logic of self-recognition in the opponent, the alter ego of the fight. One can see that the opponent is afraid, as one is afraid, that he is angry as one is angry, that he suffers, as one suffers… Inevitably, with the attention to the alter ego comes the identification, then naturally respect, and compassion.

In both practices this comes as a deeply rooted feeling, an understanding of the whole Being, not only philosophical ideas or concepts on paper : it is the beautiful strength that underlies them.

“To conquer oneself is to conquer the adversary”

Takuan Soho, 16th century Zen master

See you soon on a tatami, or a mat!

🙂

Alexander